|

AL-AHRAM WEEKLY November 20-26, 2003, Issue No. 665 Rasha Saad |

|

AL-AHRAM WEEKLY November 20-26, 2003, Issue No. 665 Rasha Saad |

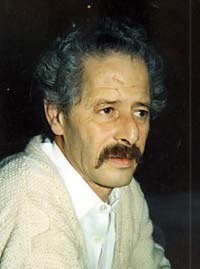

OBITUARY

Mohamed Choukri: Madman of the rosesMOROCCAN writer Mohamed Choukri died of cancer at the age of 64 Sunday morning, in Rabat's Military Hospital. Choukri had lived simply and alone in Tangiers, the setting of most of his books, rejecting the bourgeois luxuries to which his autobiographical writing had granted him access. He had been ill for many months. Born during a famine in the Rif mountains, Choukri migrated to Tetwan with his family as a small child, eventually settling in Tangiers where he engaged in a variety of jobs (one of which involved a months-long sojourn serving a French family in the Algerian Rif) to supplement his tyrannical father's meagre income. Following one of many family disputes he left the house at the age of 11, embracing a life of homelessness and petty crime. These early experiences provided him with material for his first and most famous book, Al-Khubz Al-Hafi (For Bread Alone, written in 1972 but not published in Arabic until 1982). In 1955, at the age of 20, Choukri — thief, small-time smuggler, male prostitute — managed to procure a place at a school in the desert town of Al-Ara'esh where he finally learned to read and write. Back in the cafes and whorehouses of Tangiers he began to record his personal history in standard Arabic, a language that differs appreciably from Moroccan darja, the vernacular with which, along with the Berber tongue of his birth, he was familiar. The resulting stylistic tension made for a unique idiom — mixing the cautious, correct simplicity of a secondary-school student's essay with the kind of elaborate, vernacular lyricism that characterises the best of the (Egyptian) generation of the Sixties. The prestigious Beirut monthly Al- Aadab published his first short story, Al-Unf ala Al-Shati' (Violence on the Beach) in 1966. In the 1960s Choukri also began associating with hippies who had settled in Tangiers, benefiting from the city's cosmopolitan community and meeting writers like Paul Bowels, [sic - Bowles] Tennessee Williams and, perhaps most notably, Jean Genet. (He wrote delightful accounts of his encounters with all three of them.) Eventually the project initiated in Al-Khubz Al-Hafi found expression in one more volume of autobiography, Zaman Al- Akhtaa aw Al-Shuttar (Time of Mistakes or the Streetwise, 1992), three collections of open-ended texts — Majnoun Al-Ward (Madman of the Roses, 1979); Al-Khaima (The Tent, 1985); and Al-Souq Al-Dakhili (The Inner Market, 1985) — as well as a play, Al-Saada (Happiness, 1994), and a series of reflections on literature, Ghuwayat Al-Sharour Al-Abyad (Temptation of the White Blackbird, 1998). The engaging vitality of his style notwithstanding, it is Choukri's subject matter that constitutes a major achievement — no one in Arabic literature had presented first-hand experience of street life with such unmediated honesty. Straightforward, articulate and intimately expressed, his texts are almost miraculously free of tragic inflection; populated by prostitutes, thieves and strongmen, they are under the influence of neither ideology nor morality. Reading Choukri is comparable to reading Genet: it is like entering a hothouse, a form of realism that, rather than inducing a sense of verisimilitude, acts to engulf the reader's psyche in an alternative, compelling and ultimately dissimilar network of relations. Where Choukri differs from Genet, however, is in his aversion to mythologysing. Though characters may acquire dramatically justified larger-than-life proportions they are never turned into symbols. Nor is the sometimes agonising daily process of finding enough food on which to survive and locating an appropriately safe space in which to sleep endowed with any (illusory) grandeur. Dispossession emerges all the more clearly, its constituent elements — extended, minute descriptions of the workings of hunger on body and mind, and the techniques resorted to ameliorate its pain, for example — presented as given, physical precepts that do not stand in for any grander thoughts or emotions. More provocatively for many Arab commentators, Choukri tends to call a spade a spade. With reference to the emotions of his characters, in particular, he conveys a remarkably credible range of concerns — love, which is often contemplated in its own right, never stands in for sex, an activity Choukri relates to in much the same way as eating. Genitalia take up as much space as cheap restaurants and are treated with the same open, precise and shameless interest. Historically speaking the reality of living in the Arab world is exposed for what it is — children foraging for food in the cemeteries. Choukri never loses sight of the human element, however; and those who appear in his books are more than props for an extended monodrama — their hopes and fears, their idiosyncrasies, their varying capacities for kindness and cruelty are brought to the fore and illuminated with dispassionate sympathy — so much so that they acquire a very lifelike presence, like people the reader has met or could meet. Choukri's autobiographical approach is in fact far from egocentric: he does not abandon his sense of identity as an emergent human being capable of literate self expression — the true subject of his books — but nor does he turn himself into a representative entity. His struggle, his story is in the end the mechanism that enables him to gain access to a vast and often unexpressed portion of humanity — his lifelong, so called lowly company. Choukri continued to embrace that company till the end of his life, refusing to give in to the temptation of fame and (relative) fortune, rearing a stray dog and keeping away from amorous commitment or family life while living in the company of a servant, Fathia, whose financial future he provided for prior to his death. Choukri's fascination with mortality found unexpected expression the night before he died. He had regained some strength following a minor operation and, visited by his friends Abdel- Hamid Aqqar, Hassan Najmi and Kamal Al-Khamleeshi, proved an entertaining host, telling them jokes and spreading an aura of optimism and joviality, it is reported. His breathing had steadied, and he was no longer subject to fits of violent coughing. He ate the fruit Al-Khamleeshi had brought him with relish and took notes in a little, as yet unexplored notebook by his bedside. Following the friends' departure late at night Choukri suffered an onslaught of pain, which began at four in the morning, signalling the internal haemorrhage that was to take his life at 9am on Sunday. On Monday Choukri was buried at the Marshan Cemetary, towards the city centre in Tangiers — one of his haunts as a teenager. © Copyright Al-Ahram Weekly. All rights reserved. |

![[World 2003]](world2003crm.gif)

|

![[News by region]](../regioncrm.gif)

|

![[News by topic]](../topiccrm.gif)

|

|

Created: January 5, 2004 Last modified: January 17, 2004 |

|

Commercial Sex Information Service Box 3075, Vancouver, BC V6B 3X6 Tel: +1 (604) 488-0710 Email: csis@walnet.org |